|

|

|

|

|

| Mercury | Venus | Earth | Mars | Jupiter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Saturn | Uranus | Neptune | Pluto | Small Bodies |

|

|

When you see the NASA Photojournal button, you may link to further information about the image, and a variety of image download options. |

Responsible NASA Official: PDS Engineering Node Manager: Dan Crichton

Site Manager: Betty Sword

Contact Information: PDS Operator: Colleen Schroeder

Copyright information

Last Updated: 5/10/05

Site Manager: Betty Sword

Contact Information: PDS Operator: Colleen Schroeder

Copyright information

Last Updated: 5/10/05

Planet

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the astronomical object. For other uses, see Planet (disambiguation).

The planets were thought by Ptolemy to orbit the Earth in deferent and epicycle motions. Though the idea that the planets orbited the Sun had been suggested many times, it was not until the 17th century that this view was supported by evidence from the first telescopic astronomical observations, performed by Galileo Galilei. By careful analysis of the observation data, Johannes Kepler found the planets' orbits to be not circular, but elliptical. As observational tools improved, astronomers saw that, like Earth, the planets rotated around tilted axes, and some shared such features as ice caps and seasons. Since the dawn of the Space Age, close observation by probes has found that Earth and the other planets share characteristics such as volcanism, hurricanes, tectonics, and even hydrology.

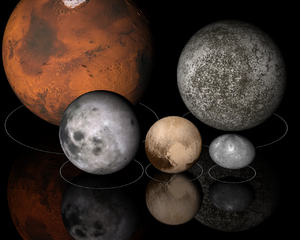

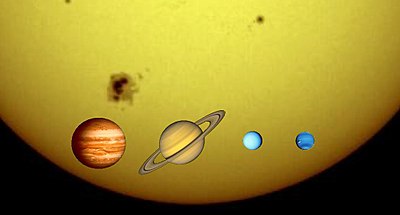

Planets are generally divided into two main types: large, low-density gas giants, and smaller, rocky terrestrials. Under IAU definitions, there are eight planets in the Solar System. In order of increasing distance from the Sun, they are the four terrestrials, Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, then the four gas giants, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Six of the planets are orbited by one or more natural satellites. Additionally, the Solar System also contains at least five dwarf planets[3] and hundreds of thousands of small Solar System bodies.

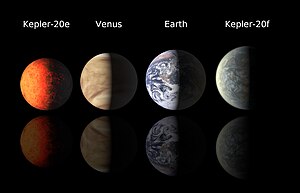

Since 1992, hundreds of planets around other stars ("extrasolar planets" or "exoplanets") in the Milky Way Galaxy have been discovered. As of February 14, 2012, 760 known extrasolar planets (in 609 planetary systems and 100 multiple planetary systems) are listed in the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia, ranging in size from that of terrestrial planets similar to Earth to that of gas giants larger than Jupiter.[4] On December 20, 2011, the Kepler Space Telescope team reported the discovery of the first Earth-sized extrasolar planets, Kepler-20e[5] and Kepler-20f,[6] orbiting a Sun-like star, Kepler-20.[7][8][9] A 2012 study, analyzing gravitational microlensing data, estimates an average of at least 1.6 bound planets for every star in the Milky Way.[10]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] History

Further information: History of astronomy and Definition of planet

See also: Timeline of solar system astronomy

The idea of planets has evolved over its history, from the divine wandering stars

of antiquity to the earthly objects of the scientific age. The concept

has expanded to include worlds not only in the Solar System, but in

hundreds of other extrasolar systems. The ambiguities inherent in

defining planets have led to much scientific controversy.The five classical planets, being visible to the naked eye, have been known since ancient times, and have had a significant impact on mythology, religious cosmology, and ancient astronomy. In ancient times, astronomers noted how certain lights moved across the sky in relation to the other stars. Ancient Greeks called these lights πλάνητες ἀστέρες (planetes asteres "wandering stars") or simply "πλανήτοι" (planētoi "wanderers"),[11] from which today's word "planet" was derived.[12][13] In ancient Greece, China, Babylon and indeed all pre-modern civilisations,[14][15] it was almost universally believed that Earth was in the center of the Universe and that all the "planets" circled the Earth. The reasons for this perception were that stars and planets appeared to revolve around the Earth each day,[16] and the apparently common-sense perception that the Earth was solid and stable, and that it was not moving but at rest.

The name for planets in Chinese astronomy had the same motive as the Greek name, 行星 "moving star". In Japanese during the Edo period there were two competing terms, 惑星 "confused star" and 遊星 "wandering star". In modern Japan, terminology was unified in favour of 惑星, but in science fiction the alternative term 遊星 retains some currency.[citation needed]

[edit] Babylon

Main article: Babylonian astronomy

The first civilization known to possess a functional theory of the planets were the Babylonians, who lived in Mesopotamia in the first and second millennia BC. The oldest surviving planetary astronomical text is the Babylonian Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa,

a 7th century BC copy of a list of observations of the motions of the

planet Venus, that probably dates as early as the second millennium BC.[17] The MUL.APIN is a pair of cuneiform tablets dating from the 7th century BC that lays out the motions of the Sun, Moon and planets over the course of the year.[18] The Babylonian astrologers also laid the foundations of what would eventually become Western astrology.[19] The Enuma anu enlil, written during the Neo-Assyrian period in the 7th century BC,[20] comprises a list of omens and their relationships with various celestial phenomena including the motions of the planets.[21][22] Venus, Mercury and the outer planets Mars, Jupiter and Saturn were all identified by Babylonian astronomers. These would remain the only known planets until the invention of the telescope in early modern times.[23][edit] Greco-Roman astronomy

See also: Greek astronomy

| 1 Moon |

2 Mercury |

3 Venus |

4 Sun |

5 Mars |

6 Jupiter |

7 Saturn |

By the 1st century BC, during the Hellenistic period, the Greeks had begun to develop their own mathematical schemes for predicting the positions of the planets. These schemes, which were based on geometry rather than the arithmetic of the Babylonians, would eventually eclipse the Babylonians' theories in complexity and comprehensiveness, and account for most of the astronomical movements observed from Earth with the naked eye. These theories would reach their fullest expression in the Almagest written by Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE. So complete was the domination of Ptolemy's model that it superseded all previous works on astronomy and remained the definitive astronomical text in the Western world for 13 centuries.[17][25] To the Greeks and Romans there were seven known planets, each presumed to be circling the Earth according to the complex laws laid out by Ptolemy. They were, in increasing order from Earth (in Ptolemy's order): the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.[13][25][26]

[edit] India

Main articles: Indian astronomy and Hindu cosmology

In 499 CE, the Indian astronomer Aryabhata propounded a planetary model which explicitly incorporated the Earth's rotation

about its axis, which he explains as the cause of what appears to be an

apparent westward motion of the stars. He also believed that the orbit

of planets are elliptical.[unreliable source?][27] Aryabhata's followers were particularly strong in South India,

where his principles of the diurnal rotation of the earth, among

others, were followed and a number of secondary works were based on

them.[28][page needed]In 1500, Nilakantha Somayaji of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics, in his Tantrasangraha, revised Aryabhata's model.[29][citation needed][30] In his Aryabhatiyabhasya, a commentary on Aryabhata's Aryabhatiya, he developed a planetary model where Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn orbit the Sun, which in turn orbits the Earth, similar to the Tychonic system later proposed by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century. Most astronomers of the Kerala school who followed him accepted his planetary model.[29][citation needed][30][31]

[edit] Medieval Muslim astronomy

Main articles: Astronomy in medieval Islam and Islamic cosmology

In the 11th century, the transit of Venus was observed by Avicenna, who established that Venus was, at least sometimes, below the Sun.[32] In the 12th century, Ibn Bajjah observed "two planets as black spots on the face of the Sun," which was later identified as a transit of Mercury and Venus by the Maragha astronomer Qotb al-Din Shirazi in the 13th century.[33] However, Ibn Bajjah could not have observed a transit of Venus, as none occurred in his lifetime.[34][edit] European Renaissance

| 1 Mercury |

2 Venus |

3 Earth |

4 Mars |

5 Jupiter |

6 Saturn |

See also: Heliocentrism

With the advent of the Scientific Revolution, understanding of the term "planet" changed from something that moved across the sky (in relation to the star field);

to a body that orbited the Earth (or that were believed to do so at the

time); and in the 16th century to something that directly orbited the

Sun when the heliocentric model of Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler gained sway.Thus the Earth became included in the list of planets,[35] while the Sun and Moon were excluded. At first, when the first satellites of Jupiter and Saturn were discovered in the 17th century, the terms "planet" and "satellite" were used interchangeably – although the latter would gradually become more prevalent in the following century.[36] Until the mid-19th century, the number of "planets" rose rapidly since any newly discovered object directly orbiting the Sun was listed as a planet by the scientific community.

[edit] 19th century

| 1 Mercury |

2 Venus |

3 Earth |

4 Mars |

5 Vesta |

6 Juno |

7 Ceres |

8 Pallas |

9 Jupiter |

10 Saturn |

11 Uranus |

[edit] 20th century

| 1 Mercury |

2 Venus |

3 Earth |

4 Mars |

5 Jupiter |

6 Saturn |

7 Uranus |

8 Neptune |

| 1 Mercury |

2 Venus |

3 Earth |

4 Mars |

5 Jupiter |

6 Saturn |

7 Uranus |

8 Neptune |

9 Pluto |

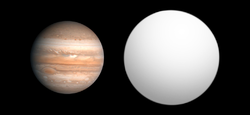

The discovery of extrasolar planets led to another ambiguity in defining a planet; the point at which a planet becomes a star. Many known extrasolar planets are many times the mass of Jupiter, approaching that of stellar objects known as "brown dwarfs".[44] Brown dwarfs are generally considered stars due to their ability to fuse deuterium, a heavier isotope of hydrogen. While stars more massive than 75 times that of Jupiter fuse hydrogen, stars of only 13 Jupiter masses can fuse deuterium. However, deuterium is quite rare, and most brown dwarfs would have ceased fusing deuterium long before their discovery, making them effectively indistinguishable from supermassive planets.[45]

[edit] 21st century

With the discovery during the latter half of the 20th century of more objects within the Solar System and large objects around other stars, disputes arose over what should constitute a planet. There was particular disagreement over whether an object should be considered a planet if it was part of a distinct population such as a belt, or if it was large enough to generate energy by the thermonuclear fusion of deuterium.A growing number of astronomers argued for Pluto to be declassified as a planet, since many similar objects approaching its size had been found in the same region of the Solar System (the Kuiper belt) during the 1990s and early 2000s. Pluto was found to be just one small body in a population of thousands.

Some of them including Quaoar, Sedna, and Eris were heralded in the popular press as the tenth planet, failing however to receive widespread scientific recognition. The announcement of Eris in 2005, an object 27% more massive than Pluto, created the necessity and public desire for an official definition of a planet.

Acknowledging the problem, the IAU set about creating the definition of planet, and produced one in August 2006. The number of planets dropped to the eight significantly larger bodies that had cleared their orbit (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune), and a new class of dwarf planets was created, initially containing three objects (Ceres, Pluto and Eris).[46]

[edit] Extrasolar planet definition

In 2003, The International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group on Extrasolar Planets made a position statement on the definition of a planet that incorporated the following working definition, mostly focused upon the boundary between planets and brown dwarfs:[2]- Objects with true masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium (currently calculated to be 13 times the mass of Jupiter for objects with the same isotopic abundance as the Sun[47]) that orbit stars or stellar remnants are "planets" (no matter how they formed). The minimum mass and size required for an extrasolar object to be considered a planet should be the same as that used in the Solar System.

- Substellar objects with true masses above the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are "brown dwarfs", no matter how they formed or where they are located.

- Free-floating objects in young star clusters with masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are not "planets", but are "sub-brown dwarfs" (or whatever name is most appropriate).

One definition of a sub-brown dwarf is a planet-mass object that formed through cloud-collapse rather than accretion. This formation distinction between a sub-brown dwarf and a planet is not universally agreed upon; astronomers are divided into two camps as whether to consider the formation process of a planet as part of its division in classification.[50] One reason for the dissent is that oftentimes it may not be possible to determine the formation process: for example an accretion-formed planet around a star may get ejected from the system to become free-floating, and likewise a cloud-collapse-formed sub-brown dwarf formed on its own in a star cluster may get captured into orbit around a star.

| Ceres | Pluto | Makemake | Haumea | Eris |

Another criterion for separating planets and brown dwarfs, rather than deuterium burning, formation process or location is whether the core pressure is dominated by coulomb pressure or electron degeneracy.[52][53]

[edit] 2006 definition

Main article: IAU definition of planet

The matter of the lower limit was addressed during the 2006 meeting of the IAU's General Assembly.

After much debate and one failed proposal, the assembly voted to pass a

resolution that defined planets within the Solar System as:[1]A celestial body that is (a) in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.Under this definition, the Solar System is considered to have eight planets. Bodies which fulfill the first two conditions but not the third (such as Pluto, Makemake and Eris) are classified as dwarf planets, provided they are not also natural satellites of other planets. Originally an IAU committee had proposed a definition that would have included a much larger number of planets as it did not include (c) as a criterion.[54] After much discussion, it was decided via a vote that those bodies should instead be classified as dwarf planets.[55]

This definition is based in theories of planetary formation, in which planetary embryos initially clear their orbital neighborhood of other smaller objects. As described by astronomer Steven Soter:[56]

The end product of secondary disk accretion is a small number of relatively large bodies (planets) in either non-intersecting or resonant orbits, which prevent collisions between them. Asteroids and comets, including KBOs [Kuiper belt objects], differ from planets in that they can collide with each other and with planets.In the aftermath of the IAU's 2006 vote, there has been controversy and debate about the definition,[57][58] and many astronomers have stated that they will not use it.[59] Part of the dispute centres around the belief that point (c) (clearing its orbit) should not have been listed, and that those objects now categorised as dwarf planets should actually be part of a broader planetary definition.

Beyond the scientific community, Pluto has held a strong cultural significance for many in the general public considering its planetary status since its discovery in 1930. The discovery of Eris was widely reported in the media as the tenth planet and therefore the reclassification of all three objects as dwarf planets has attracted a lot of media and public attention as well.[60]

[edit] Former classifications

The table below lists Solar System bodies formerly considered to be planets:| Body (current classification) | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Star | Dwarf planet | Asteroid | Moon | |

| Sun | The Moon | Classified as planets in antiquity, in accordance with the definition then used. | ||

| Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto | The four largest moons of Jupiter, known as the Galilean moons after their discoverer Galileo Galilei. He referred to them as the "Medicean Planets" in honor of his patron, the Medici family. | |||

| Titan,[b] Iapetus,[c] Rhea,[c] Tethys,[d] and Dione[d] | Five of Saturn's larger moons, discovered by Christiaan Huygens and Giovanni Domenico Cassini. | |||

| Ceres[e] | Pallas, Juno, and Vesta | The first known asteroids, from their discoveries between 1801 and 1807 until their reclassification as asteroids during the 1850s.[61] Ceres has subsequently been classified as a dwarf planet in 2006. | ||

| Astrea, Hebe, Iris, Flora, Metis, Hygeia, Parthenope, Victoria, Egeria, Irene, Eunomia | More asteroids, discovered between 1845 and 1851. The rapidly expanding list of planets prompted their reclassification as asteroids by astronomers, and this was widely accepted by 1854.[62] | |||

| Pluto[f] | The first known Trans-Neptunian object (i.e. minor planet with a semi-major axis beyond Neptune). In 2006, Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet. | |||

| Eris (dwarf planet) (originally nicknamed Xena) | Discovered in 2003, this Trans-Neptunian object (i.e. minor planet with a semi-major axis beyond Neptune) was recognised in 2005, before, like Pluto, in 2006 getting reclassified as a dwarf planet. | |||

[edit] Mythology and naming

See also: Weekday names and Naked-eye planet

The Greek practice of grafting of their gods' names onto the planets was almost certainly borrowed from the Babylonians. The Babylonians named Phosphoros after their goddess of love, Ishtar; Pyroeis after their god of war, Nergal, Stilbon after their god of wisdom Nabu, and Phaethon after their chief god, Marduk.[63] There are too many concordances between Greek and Babylonian naming conventions for them to have arisen separately.[17] The translation was not perfect. For instance, the Babylonian Nergal was a god of war, and thus the Greeks identified him with Ares. However, unlike Ares, Nergal was also god of pestilence and the underworld.[64]

Today, most people in the western world know the planets by names derived from the Olympian pantheon of gods. While modern Greeks still use their ancient names for the planets, other European languages, because of the influence of the Roman Empire and, later, the Catholic Church, use the Roman (or Latin) names rather than the Greek ones. The Romans, who, like the Greeks, were Indo-Europeans, shared with them a common pantheon under different names but lacked the rich narrative traditions that Greek poetic culture had given their gods. During the later period of the Roman Republic, Roman writers borrowed much of the Greek narratives and applied them to their own pantheon, to the point where they became virtually indistinguishable.[65] When the Romans studied Greek astronomy, they gave the planets their own gods' names: Mercurius (for Hermes), Venus (Aphrodite), Mars (Ares), Iuppiter (Zeus) and Saturnus (Cronus). When subsequent planets were discovered in the 18th and 19th centuries, the naming practice was retained with Neptūnus (Poseidon). Uranus is unique in that it is named by a Greek deity rather than his Roman counterpart.

Some Romans, following a belief possibly originating in Mesopotamia but developed in Hellenistic Egypt, believed that the seven gods after whom the planets were named took hourly shifts in looking after affairs on Earth. The order of shifts went Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Sun, Venus, Mercury, Moon (from the farthest to the closest planet).[66] Therefore, the first day was started by Saturn (1st hour), second day by Sun (25th hour), followed by Moon (49th hour), Mars, Mercury, Jupiter and Venus. Since each day was named by the god that started it, this is also the order of the days of the week in the Roman calendar after the Nundinal cycle was rejected – and still preserved in many modern languages.[67] Sunday, Monday, and Saturday are straightforward translations of these Roman names. In English the other days were renamed after Tiw, (Tuesday) Wóden (Wednesday), Thunor (Thursday), and Fríge (Friday), the Anglo-Saxon gods considered similar or equivalent to Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus respectively.

Earth is the only planet whose name in English is not derived from Greco-Roman mythology. Since it was only generally accepted as a planet in the 17th century,[35] there is no tradition of naming it after a god (the same is true, in English at least, of the Sun and the Moon, though they are no longer considered planets). The name originates from the 8th century Anglo-Saxon word erda, which means ground or soil and was first used in writing as the name of the sphere of the Earth perhaps around 1300.[68][69] As with its equivalents in the other Germanic languages, it derives ultimately from the Proto-Germanic word ertho, "ground,"[69] as can be seen in the English Earth, the German Erde, the Dutch Aarde, and the Scandinavian Jord. Many of the Romance languages retain the old Roman word terra (or some variation of it) that was used with the meaning of "dry land" (as opposed to "sea").[70] However, the non-Romance languages use their own respective native words. The Greeks retain their original name, Γή (Ge or Yi).

Non-European cultures use other planetary naming systems. India uses a naming system based on the Navagraha, which incorporates the seven traditional planets (Surya for the Sun, Chandra for the Moon, and Budha, Shukra, Mangala, Bṛhaspati and Shani for the traditional planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) and the ascending and descending lunar nodes Rahu and Ketu. China and the countries of eastern Asia historically subject to Chinese cultural influence (such as Japan, Korea and Vietnam) use a naming system based on the five Chinese elements: water (Mercury), metal (Venus), fire (Mars), wood (Jupiter) and earth (Saturn).[67]

[edit] Formation

Main article: Nebular hypothesis

It is not known with certainty how planets are formed. The prevailing theory is that they are formed during the collapse of a nebula into a thin disk of gas and dust. A protostar forms at the core, surrounded by a rotating protoplanetary disk. Through accretion

(a process of sticky collision) dust particles in the disk steadily

accumulate mass to form ever-larger bodies. Local concentrations of mass

known as planetesimals

form, and these accelerate the accretion process by drawing in

additional material by their gravitational attraction. These

concentrations become ever denser until they collapse inward under

gravity to form protoplanets.[71]

After a planet reaches a diameter larger than the Earth's moon, it

begins to accumulate an extended atmosphere, greatly increasing the

capture rate of the planetesimals by means of atmospheric drag.[72]When the protostar has grown such that it ignites to form a star, the surviving disk is removed from the inside outward by photoevaporation, the solar wind, Poynting–Robertson drag and other effects.[73][74] Thereafter there still may be many protoplanets orbiting the star or each other, but over time many will collide, either to form a single larger planet or release material for other larger protoplanets or planets to absorb.[75] Those objects that have become massive enough will capture most matter in their orbital neighbourhoods to become planets. Meanwhile, protoplanets that have avoided collisions may become natural satellites of planets through a process of gravitational capture, or remain in belts of other objects to become either dwarf planets or small bodies.

The energetic impacts of the smaller planetesimals (as well as radioactive decay) will heat up the growing planet, causing it to at least partially melt. The interior of the planet begins to differentiate by mass, developing a denser core.[76] Smaller terrestrial planets lose most of their atmospheres because of this accretion, but the lost gases can be replaced by outgassing from the mantle and from the subsequent impact of comets.[77] (Smaller planets will lose any atmosphere they gain through various escape mechanisms.)

With the discovery and observation of planetary systems around stars other than our own, it is becoming possible to elaborate, revise or even replace this account. The level of metallicity – an astronomical term describing the abundance of chemical elements with an atomic number greater than 2 (helium) – is now believed to determine the likelihood that a star will have planets.[78] Hence, it is thought that a metal-rich population I star will likely possess a more substantial planetary system than a metal-poor, population II star.

[edit] Solar System

Main article: Solar System

According to the IAU, there are eight planets and five recognized dwarf planets in the Solar System. In increasing distance from the Sun, the planets are:Jupiter is the largest, at 318 Earth masses, while Mercury is smallest, at 0.055 Earth masses.

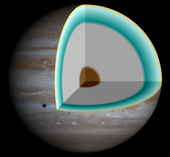

The planets of the Solar System can be divided into categories based on their composition:

- Terrestrials: Planets that are similar to Earth, with bodies largely composed of rock: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. At 0.055 Earth masses, Mercury is the smallest terrestrial planet (and smallest planet) in the Solar System, while Earth is the largest terrestrial planet.

- Gas giants (Jovians): Planets largely composed of gaseous

material and significantly more massive than terrestrials: Jupiter,

Saturn, Uranus, Neptune. Jupiter, at 318 Earth masses, is the largest

planet in the Solar System, while Saturn is one third as big, at 95

Earth masses.

- Ice giants, comprising Uranus and Neptune, are a sub-class of gas giants, distinguished from gas giants by their significantly lower mass (only 14 and 17 Earth masses), and by depletion in hydrogen and helium in their atmospheres together with a significantly higher proportion of rock and ice.

- Dwarf planets: Before the August 2006 decision, several objects were proposed by astronomers, including at one stage by the IAU, as planets. However in 2006 several of these objects were reclassified as dwarf planets, objects distinct from planets. Currently five dwarf planets in the Solar System are recognized by the IAU: Ceres, Pluto, Haumea, Makemake and Eris. Several other objects in both the Asteroid belt and the Kuiper belt are under consideration, with as many as 50 that could eventually qualify. There may be as many as 200 that could be discovered once the Kuiper belt has been fully explored. Dwarf planets share many of the same characteristics as planets, although notable differences remain – namely that they are not dominant in their orbits. By definition, all dwarf planets are members of larger populations. Ceres is the largest body in the asteroid belt, while Pluto, Haumea, and Makemake are members of the Kuiper belt and Eris is a member of the scattered disc. Scientists such as Mike Brown believe that there are probably over one hundred trans-Neptunian objects that qualify as dwarf planets under the IAU's recent definition.[79]

[edit] Planetary attributes

| Type | Name | Equatorial diameter[a] |

Mass[a] | Orbital radius (AU) |

Orbital period (years)[a] |

Inclination to Sun's equator (°) |

Orbital eccentricity |

Rotation period (days) |

Confirmed moons[c] |

Rings | Atmosphere |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial planet | Mercury | 0.382 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 3.38 | 0.206 | 58.64 | 0 | no | minimal |

| Venus | 0.949 | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 3.86 | 0.007 | −243.02 | 0 | no | CO2, N2 | |

| Earth[b] | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 7.25 | 0.017 | 1.00 | 1 | no | N2, O2 | |

| Mars | 0.532 | 0.11 | 1.52 | 1.88 | 5.65 | 0.093 | 1.03 | 2 | no | CO2, N2 | |

| Gas giant | Jupiter | 11.209 | 317.8 | 5.20 | 11.86 | 6.09 | 0.048 | 0.41 | 64 | yes | H2, He |

| Saturn | 9.449 | 95.2 | 9.54 | 29.46 | 5.51 | 0.054 | 0.43 | 62 | yes | H2, He | |

| Uranus | 4.007 | 14.6 | 19.22 | 84.01 | 6.48 | 0.047 | −0.72 | 27 | yes | H2, He | |

| Neptune | 3.883 | 17.2 | 30.06 | 164.8 | 6.43 | 0.009 | 0.67 | 13 | yes | H2, He | |

| Dwarf planet | Ceres | 0.08 | 0.000 2 | 2.5–3.0 | 4.60 | 10.59 | 0.080 | 0.38 | 0 | no | none |

| Pluto | 0.18 | 0.002 2 | 29.7–49.3 | 248.09 | 17.14 | 0.249 | −6.39 | 4 | no | temporary | |

| Haumea | 0.15×0.12 | 0.000 7 | 35.2–51.5 | 282.76 | 28.19 | 0.189 | 0.16 | 2 | ? | ? | |

| Makemake | ~0.12 | 0.000 7 | 38.5–53.1 | 309.88 | 28.96 | 0.159 | ? | 0 | ? | ? [d] | |

| Eris | 0.19 | 0.002 5 | 37.8–97.6 | ~557 | 44.19 | 0.442 | ~0.3 | 1 | ? | ? [d] |

[edit] Extrasolar planets

Main article: Extrasolar planet

In early 1992, radio astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced the discovery of two planets orbiting the pulsar PSR 1257+12.[42]

This discovery was confirmed, and is generally considered to be the

first definitive detection of exoplanets. These pulsar planets are

believed to have formed from the unusual remnants of the supernova that produced the pulsar, in a second round of planet formation, or else to be the remaining rocky cores of gas giants that survived the supernova and then decayed into their current orbits.The first confirmed discovery of an extrasolar planet orbiting an ordinary main-sequence star occurred on 6 October 1995, when Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz of the University of Geneva announced the detection of an exoplanet around 51 Pegasi. Of the 760 extrasolar planets discovered by February 14, 2012,[4] most have masses which are comparable to or larger than Jupiter's, though masses ranging from just below that of Mercury to many times Jupiter's mass have been observed.[4] The smallest extrasolar planets found to date have been discovered orbiting burned-out star remnants called pulsars, such as PSR B1257+12.[81]

There have been roughly a dozen extrasolar planets found of between 10 and 20 Earth masses,[4] such as those orbiting the stars Mu Arae, 55 Cancri and GJ 436.[82]

Another new category are the so-called "super-Earths", possibly terrestrial planets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune or Uranus. To date, about twenty possible super-Earths (depending on mass limits) have been found, including OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb and MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb, frigid icy worlds discovered through gravitational microlensing,[83][84] Kepler 10b, a planet with a diameter roughly 1.4 times that of Earth, (making it the smallest super-Earth yet measured)[85] and five of the six planets orbiting the nearby red dwarf Gliese 581. Gliese 581 d is roughly 7.7 times Earth's mass,[86] while Gliese 581 c is five times Earth's mass and was initially thought to be the first terrestrial planet found within a star's habitable zone.[87] However, more detailed studies revealed that it was slightly too close to its star to be habitable, and that the farther planet in the system, Gliese 581 d, though it is much colder than Earth, could potentially be habitable if its atmosphere contained sufficient amounts of greenhouse gases.[88] Another super-Earth, Kepler-22b, was later confirmed to be orbiting comfortably within the habitable zone of its star.[89] On December 20, 2011, the Kepler Space Telescope team reported the discovery of the first Earth-size extrasolar planets, Kepler-20e[5] and Kepler-20f,[6] orbiting a Sun-like star, Kepler-20.[7][8][9]

[edit] Planetary-mass objects

A planetary-mass object, PMO, or planemo is a celestial object with a mass that falls within the range of the definition of a planet: massive enough to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium (to be rounded under its own gravity), but not enough to sustain core fusion like a star.[95] By definition, all planets are planetary-mass objects, but the purpose of the term is to describe objects which do not conform to typical expectations for a planet. These include dwarf planets, the larger moons, free-floating planets not orbiting a star, such as rogue planets ejected from their system, and objects that formed through cloud-collapse rather than accretion (sometimes called sub-brown dwarfs).[edit] Rogue planets

Main article: Rogue planet

Several computer simulations

of stellar and planetary system formation have suggested that some

objects of planetary mass would be ejected into interstellar space.[96]

Some scientists have argued that such objects found roaming in deep

space should be classed as "planets", although others have suggested

that they could be low-mass stars.[97][98][edit] Sub-brown dwarfs

Main article: Sub-brown dwarf

Stars form via the gravitational collapse of gas clouds, but smaller

objects can also form via cloud-collapse. Planetary-mass objects formed

this way are sometimes called sub-brown dwarfs. Sub-brown dwarfs may be

free-floating such as Cha 110913-773444, or orbiting a larger object such as 2MASS J04414489+2301513.For a brief time in 2006, astronomers believed they had found a binary system of such objects, Oph 162225-240515, which the discoverers described as "planemos", or "planetary-mass objects". However, recent analysis of the objects has determined that their masses are probably each greater than 13 Jupiter-masses, making the pair brown dwarfs.[99][100][101]

[edit] Former stars

In close binary star systems one of the stars can lose mass to a heavier companion. See accretion-powered pulsars. The shrinking star can then become a planetary-mass object. An example is a Jupiter-mass object orbiting the pulsar PSR J1719-1438.[102][edit] Satellite planets and belt planets

Some large satellites are of similar size or larger than the planet Mercury, e.g. Jupiter's Galilean moons and Titan. Alan Stern has argued that location should not matter and that only geophysical attributes should be taken into account in the definition of a planet, and proposes the term satellite planet for a planet-sized satellite. Likewise, dwarf planets in the asteroid belt and Kuiper belt should be considered planets according to Stern.[103][edit] Attributes

Although each planet has unique physical characteristics, a number of broad commonalities do exist among them. Some of these characteristics, such as rings or natural satellites, have only as yet been observed in planets in the Solar System, whilst others are also common to extrasolar planets.[edit] Dynamic characteristics

See also: Kepler's laws of planetary motion

[edit] Orbit

The orbit of the planet Neptune compared to that of Pluto. Note the elongation of Pluto's orbit in relation to Neptune's (eccentricity), as well as its large angle to the ecliptic (inclination).

Each planet's orbit is delineated by a set of elements:

- The eccentricity of an orbit describes how elongated a planet's orbit is. Planets with low eccentricities have more circular orbits, while planets with high eccentricities have more elliptical orbits. The planets in the Solar System have very low eccentricities, and thus nearly circular orbits.[105] Comets and Kuiper belt objects (as well as several extrasolar planets) have very high eccentricities, and thus exceedingly elliptical orbits.[107][108]

- The semi-major axis is the distance from a planet to the half-way point along the longest diameter of its elliptical orbit (see image). This distance is not the same as its apastron, as no planet's orbit has its star at its exact centre.[105]

- The inclination of a planet tells how far above or below an established reference plane its orbit lies. In the Solar System, the reference plane is the plane of Earth's orbit, called the ecliptic. For extrasolar planets, the plane, known as the sky plane or plane of the sky, is the plane of the observer's line of sight from Earth.[109] The eight planets of the Solar System all lie very close to the ecliptic; comets and Kuiper belt objects like Pluto are at far more extreme angles to it.[110] The points at which a planet crosses above and below its reference plane are called its ascending and descending nodes.[105] The longitude of the ascending node is the angle between the reference plane's 0 longitude and the planet's ascending node. The argument of periapsis (or perihelion in the Solar System) is the angle between a planet's ascending node and its closest approach to its star.[105]

[edit] Axial tilt

Planets also have varying degrees of axial tilt; they lie at an angle to the plane of their stars' equators. This causes the amount of light received by each hemisphere to vary over the course of its year; when the northern hemisphere points away from its star, the southern hemisphere points towards it, and vice versa. Each planet therefore possesses seasons; changes to the climate over the course of its year. The time at which each hemisphere points farthest or nearest from its star is known as its solstice. Each planet has two in the course of its orbit; when one hemisphere has its summer solstice, when its day is longest, the other has its winter solstice, when its day is shortest. The varying amount of light and heat received by each hemisphere creates annual changes in weather patterns for each half of the planet. Jupiter's axial tilt is very small, so its seasonal variation is minimal; Uranus, on the other hand, has an axial tilt so extreme it is virtually on its side, which means that its hemispheres are either perpetually in sunlight or perpetually in darkness around the time of its solstices.[111] Among extrasolar planets, axial tilts are not known for certain, though most hot Jupiters are believed to possess negligible to no axial tilt, as a result of their proximity to their stars.[112][edit] Rotation

The planets rotate around invisible axes through their centres. A planet's rotation period is known as a stellar day. Most of the planets in the Solar System rotate in the same direction as they orbit the Sun, which is counter-clockwise as seen from above the sun's north pole, the exceptions being Venus[113] and Uranus[114] which rotate clockwise, though Uranus's extreme axial tilt means there are differing conventions on which of its poles is "north", and therefore whether it is rotating clockwise or anti-clockwise.[115] However, regardless of which convention is used, Uranus has a retrograde rotation relative to its orbit.The rotation of a planet can be induced by several factors during formation. A net angular momentum can be induced by the individual angular momentum contributions of accreted objects. The accretion of gas by the gas giants can also contribute to the angular momentum. Finally, during the last stages of planet building, a stochastic process of protoplanetary accretion can randomly alter the spin axis of the planet.[116] There is great variation in the length of day between the planets, with Venus taking 243 Earth days to rotate, and the gas giants only a few hours.[117] The rotational periods of extrasolar planets are not known; however their proximity to their stars means that hot Jupiters are tidally locked (their orbits are in sync with their rotations). This means they only ever show one face to their stars, with one side in perpetual day, the other in perpetual night.[118]

[edit] Orbital clearing

The defining dynamic characteristic of a planet is that it has cleared its neighborhood. A planet that has cleared its neighborhood has accumulated enough mass to gather up or sweep away all the planetesimals in its orbit. In effect, it orbits its star in isolation, as opposed to sharing its orbit with a multitude of similar-sized objects. This characteristic was mandated as part of the IAU's official definition of a planet in August, 2006. This criterion excludes such planetary bodies as Pluto, Eris and Ceres from full-fledged planethood, making them instead dwarf planets.[1] Although to date this criterion only applies to the Solar System, a number of young extrasolar systems have been found in which evidence suggests orbital clearing is taking place within their circumstellar discs.[119][edit] Physical characteristics

[edit] Mass

A planet's defining physical characteristic is that it is massive enough for the force of its own gravity to dominate over the electromagnetic forces binding its physical structure, leading to a state of hydrostatic equilibrium. This effectively means that all planets are spherical or spheroidal. Up to a certain mass, an object can be irregular in shape, but beyond that point, which varies depending on the chemical makeup of the object, gravity begins to pull an object towards its own centre of mass until the object collapses into a sphere.[120]Mass is also the prime attribute by which planets are distinguished from stars. The upper mass limit for planethood is roughly 13 times Jupiter's mass for objects with solar-type isotopic abundance, beyond which it achieves conditions suitable for nuclear fusion. Other than the Sun, no objects of such mass exist in the Solar System; but there are exoplanets of this size. The 13MJ limit is not universally agreed upon and the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia includes objects up to 20 Jupiter masses,[121] and the Exoplanet Data Explorer up to 24 Jupiter masses.[122]

The smallest known planet, excluding dwarf planets and satellites, is PSR B1257+12A, one of the first extrasolar planets discovered, which was found in 1992 in orbit around a pulsar. Its mass is roughly half that of the planet Mercury.[4] The smallest planet orbiting a main-sequence star other than the Sun is Kepler-20e, with a mass roughly similar to that of Venus.

[edit] Internal differentiation

[edit] Atmosphere

See also: Extraterrestrial atmospheres

All of the Solar System planets have atmospheres

as their large masses mean gravity is strong enough to keep gaseous

particles close to the surface. The larger gas giants are massive enough

to keep large amounts of the light gases hydrogen and helium close by, while the smaller planets lose these gases into space.[126] The composition of the Earth's atmosphere is different from the other planets because the various life processes that have transpired on the planet have introduced free molecular oxygen.[127]

The only solar planet without a substantial atmosphere is Mercury which

had it mostly, although not entirely, blasted away by the solar wind.[128]Planetary atmospheres are affected by the varying degrees of energy received from either the Sun or their interiors, leading to the formation of dynamic weather systems such as hurricanes, (on Earth), planet-wide dust storms (on Mars), an Earth-sized anticyclone on Jupiter (called the Great Red Spot), and holes in the atmosphere (on Neptune).[111] At least one extrasolar planet, HD 189733 b, has been claimed to possess such a weather system, similar to the Great Red Spot but twice as large.[129]

Hot Jupiters have been shown to be losing their atmospheres into space due to stellar radiation, much like the tails of comets.[130][131] These planets may have vast differences in temperature between their day and night sides which produce supersonic winds,[132] although the day and night sides of HD 189733 b appear to have very similar temperatures, indicating that that planet's atmosphere effectively redistributes the star's energy around the planet.[129]

[edit] Magnetosphere

Of the eight planets in the Solar System, only Venus and Mars lack such a magnetic field.[133] In addition, the moon of Jupiter Ganymede also has one. Of the magnetized planets the magnetic field of Mercury is the weakest, and is barely able to deflect the solar wind. Ganymede's magnetic field is several times larger, and Jupiter's is the strongest in the Solar System (so strong in fact that it poses a serious health risk to future manned missions to its moons). The magnetic fields of the other giant planets are roughly similar in strength to that of Earth, but their magnetic moments are significantly larger. The magnetic fields of Uranus and Neptune are strongly tilted relative the rotational axis and displaced from the centre of the planet.[133]

In 2004, a team of astronomers in Hawaii observed an extrasolar planet around the star HD 179949, which appeared to be creating a sunspot on the surface of its parent star. The team hypothesised that the planet's magnetosphere was transferring energy onto the star's surface, increasing its already high 7,760 °C temperature by an additional 400 °C.[134]

[edit] Secondary characteristics

Several planets or dwarf planets in the Solar System (such as Neptune and Pluto) have orbital periods that are in resonance with each other or with smaller bodies (this is also common in satellite systems). All except Mercury and Venus have natural satellites, often called "moons". Earth has one, Mars has two, and the gas giants have numerous moons in complex planetary-type systems. Many gas giant moons have similar features to the terrestrial planets and dwarf planets, and some have been studied as possible abodes of life (especially Europa).[135][136][137]No secondary characteristics have been observed around extrasolar planets. However the sub-brown dwarf Cha 110913-773444, which has been described as a rogue planet, is believed to be orbited by a tiny protoplanetary disc.[97]

[edit] Related terms

- Comet

- Double planet

- Dwarf planet

- Extrasolar planet (or Exoplanet) – celestial body outside the Solar System

- Mesoplanet

- Minor planet – celestial body smaller than a planet

- Planetar (astronomy)

- Planetary mnemonic

- Planetesimal

- Protoplanet

- Rogue planet

[edit] See also

[edit

Sri Lanka

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Ceylon" redirects here. For the time period of 1948-1972, see Dominion of Ceylon. For other uses, see Ceylon (disambiguation).

|

||||||

| Anthem:

Sri Lanka Matha Mother Sri Lanka |

||||||

| Capital | Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte[1][2] 6°54′N 79°54′E |

|||||

| Largest city | Colombo | |||||

| Official language(s) | Sinhala Tamil |

|||||

| Demonym | Sri Lankan | |||||

| Government | Unitary republic Democratic Socialist Semi-presidential system |

|||||

| - | President | Mahinda Rajapaksa | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | D. M. Jayaratne | ||||

| - | Speaker of the House | Chamal Rajapaksa | ||||

| - | Chief Justice | Dr. Shirani Bandaranayake | ||||

| Independence | from the United Kingdom | |||||

| - | Dominion (Self rule) | February 4, 1948 | ||||

| - | Republic | May 22, 1972 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 65,610 km2 (122nd) 25,332 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 4.4 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2010 estimate | 20,238,000[3] (56th) | ||||

| - | Mid 2010 census | 20,653,000[4] | ||||

| - | Density | 308.5/km2 (35th) 798.9/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $106.5 billion[5] (65th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $5,220[5] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $49.68 billion[5] (73rd) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $2,435[5] | ||||

| Gini (2010) | 36[6] (medium) | |||||

| HDI (2011) | ||||||

| Currency | Sri Lankan Rupee (LKR) |

|||||

| Time zone | Sri Lanka Standard Time Zone (UTC+5:30) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC) | ||||

| Date formats | dd/mm/yy, dd/mm/yyyy, yyyy/mm/dd (AD) | |||||

| Drives on the | left | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | LK | |||||

| Internet TLD | .lk, .ලංකා, .இலங்கை | |||||

| Calling code | 94 | |||||

As a result of its location in the path of major sea routes, Sri Lanka is a strategic naval link between West Asia and South East Asia.[10] It was an important stop on the ancient Silk Road.[11] Sri Lanka has also been a center of the Buddhist religion and culture from ancient times, and is one of the few remaining abodes of Buddhism in South Asia along with Ladakh, Bhutan and the Chittagong hill tracts.[12] The Sinhalese community forms the majority of the population; Tamils, who are concentrated in the north and east of the island, form the largest ethnic minority. Other communities include Moors, Burghers, Kaffirs, Malays and the aboriginal Vedda people.[13]

Sri Lanka is a republic and a unitary state which is governed by a semi-presidential system with its official seat of government in Sri Jayawardenapura-Kotte, the capital. The country is famous for the production and export of tea, coffee, coconuts, rubber and cinnamon, the last of which is native to the country.[14] The natural beauty of Sri Lanka has led to the title The Pearl of the Indian Ocean.[15] The island is laden with lush tropical forests, white beaches and diverse landscapes with rich biodiversity. The country lays claim to a long and colorful history of over three thousand years, having one of the longest documented histories in the world.[16] Sri Lanka's rich culture can be attributed to the many different communities on the island.[17]

Sri Lanka is a founding member state of SAARC and a member United Nations, Commonwealth of Nations, G77 and Non-Aligned Movement. As of 2010, Sri Lanka was one of the fastest growing economies of the world. Its stock exchange was Asia's best performing stock market during 2009 and 2010.[18]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Etymology

Main article: Names of Sri Lanka

In ancient times, Sri Lanka was known by a variety of names: Known in

India as Lanka or Singhala, ancient Greek geographers called it Taprobane[19] In Sinhala the country is known as ශ්රී ලංකා śrī laṃkā, IPA: [ʃɾiːˈlaŋkaː], and the island itself as ලංකාව laṃkāva, IPA: [laŋˈkaːʋə]. In Tamil they are both இலங்கை ilaṅkai, IPA: [iˈlaŋɡai]. The name derives from the Sanskrit श्री लंका śrī (venerable) and lankā (island),[23] the name of the island in the ancient Indian epics Mahabharata and the Ramayana. In 1972, the official name of the country was changed to "Free, Sovereign and Independent Republic of Sri Lanka". In 1978 it was changed to the "Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka".[24] The name Ceylon is still in use in the names of a number of organisations; in 2011, the Sri Lankan government announced a plan to rename all of those for which it is responsible.[25]

[edit] History

Main article: History of Sri Lanka

[edit] Pre-historic Sri Lanka

Main article: Prehistory of Sri Lanka

The pre-history of Sri Lanka dates back over 125,000 years Before Present (BP) and possibly even as early as 500,000 BP.[26] The era spans the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and early Iron ages. Among the Paleolithic (Homo Erectus) human settlements discovered in Sri Lanka, Pahiyangala (named after the Chinese traveler monk Fa-Hsien), which dates back to 37,000 BP,[27] Batadombalena (28,500 BP)[28] and Belilena (12,000 BP) are the most important. The remains of Balangoda Man, an anatomically modern human, found inside these caves,[29] suggests that they may have engaged in agriculture and kept domestic dogs for driving game.[30]Ravana belonged to the tribe Raksha, which lived alongside four Hela tribes named Yaksha, Deva, Naga and Gandharva.[34] These early inhabitants of Sri Lanka were probably the ancestors of the Vedda people,[35] an indigenous community living in modern-day Sri Lanka, which numbers approximately 2,500. Irish historian James Emerson Tennent theorised Galle, a southern city in Sri Lanka, was the ancient seaport of Tarshish, from which King Solomon is said to have drawn ivory, peacocks and other valuables. Early inhabitats of the country spoke the Elu language, which is considered the early form of the modern Sinhala language.[36]

[edit] Ancient Sri Lanka

Main article: Ancient history of Sri Lanka

According to the Mahāvamsa, a chronicle written in Pāli language, the ancient period of Sri Lanka begins in 543 BC with the landing of Vijaya, a semi-legendary king who arrived in the country with 700 followers from the southwest coast of what is now the Rarh region of West Bengal.[37] He established the Kingdom of Tambapanni, near modern day Mannar. Vijaya is the first of the approximately 189 native monarchs of Sri Lanka, the chronicles like Dipavamsa, Mahāvamsa, Chulavamsa and Rājāvaliya describe. (see List of Sri Lankan monarchs) Sri Lankan dynasty spanned over a period of 2359 years, from 543 BC to 1815 AD, until it came under the rule of British Empire.[38]Sri Lanka experienced the first foreign invasion during the reign of Suratissa, who was defeated by two horse traders named Sena and Guttika from South India.[43] The next invasion came immediately in 205 BC by a Chola king named Elara, who overthrew Asela and ruled the country for 44 years. Dutugemunu, the eldest son of the southern regional sub-king, Kavan Tissa, defeated Elara in the Battle of Vijithapura. He built Ruwanwelisaya, the second stupa in ancient Sri Lanka, and the Lovamahapaya.[47] During its two and half millenias of existence, kingdom of Sri Lanka was invaded at least 8 times by neighbouring South Asian dynastys such as Chola, Pandya, Chera and Pallava.[48] There had also been incursions by the kingdoms of Kalinga (modern Orissa) and from Malay Peninsula as well. Kala Wewa and the Avukana Buddha statue were built during the reign of Dhatusena.[49]

[edit] Medieval Sri Lanka

Main article: Medieval history of Sri Lanka

After his demise, Sri Lanka gradually decayed in power. In 1215 AD, Kalinga Magha, a South Indian with uncertain origins, invaded and captured the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa with a 24,000 strong army from Kalinga.[65] Unlike the previous invaders, he looted, ransacked and destroyed everything in the ancient Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa Kingdoms beyond recovery.[68] His priorities in ruling were to extract as much as possible from the land and overturn as many of the traditions of Rajarata as possible. His reign saw the massive migration of native Sinhalese people to the south and west of Sri Lanka, and into the mountainous interior, in a bid to escape his power. Sri Lanka never really recovered from the impact of Kalinga Magha's invasion. King Vijayabâhu III, who led the resistance, brought the kingdom to Dambadeniya. The north, in the meanwhile, eventually evolved into the Jaffna kingdom.[69][70] Jaffna kingdom never came under the rule of the kingdom of south except on one occasion; in 1450, following the conquest led by king Parâkramabâhu VI's adopted son, Prince Sapumal.[71] He ruled the North from 1450 to 1467 AD.[72] The next three centuries stating from 1215 were marked by kaleidoscopically shifting collection of kingdoms in south and central Sri Lanka, including Dambadeniya, Yapahuwa, Gampola, Raigama, Kotte,[73] Sitawaka and finally, Kandy.

[edit] Early modern Sri Lanka

Main article: Colonial history of Sri Lanka

During the Napoleonic Wars, fearing that French control of the Netherlands might deliver Sri Lanka to the French, Great Britain occupied the coastal areas of the island (which they called Ceylon) with little difficulty in 1796.[82] Two years later, in 1798, Rajadhi Rajasinha, 3rd of the four Nayakkar kings of Sri Lanka died of a fever. Following the death, a nephew of Rajadhi Rajasinha, 18-year-old Konnasami was crowned.[83] The new king, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha faced a British invasion in 1803, but was able to retaliate successfully. By then, the entire coastal area was under the British East India Company, as a result of the Treaty of Amiens. But on 14 February 1815, Kandy was occupied by the British, in the second Kandyan War, finally ending Sri Lanka's independence.[83] Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, the last native monarch of Sri Lanka was exiled to India.[84] Kandyan convention formally ceded the entire country to the British Empire. Attempts of Sri Lankan noblemen to undermine the British power in 1818 during the Uva Rebellion were thwarted by Governor Robert Brownrigg.[85]

[edit] Modern Sri Lanka

[edit] Sri Lanka under the British rule

By the end of the 19th century, a new educated social class which transcended the divisions of race and caste was emerging as a result of British attempts to nurture a range of professionals for the Ceylon Civil Service and for the legal, educational, and medical professions.[89] The country's new leaders represented the various ethnic groups of the population in the Ceylon Legislative Council on a communal basis. In the meantime, attempts were underway for Buddhist and Hindu revivalism and to react against Christian missionary activities on the island.[90][91] The first two decades in the 20th century are distinguished for the harmony that prevailed among Sinhalese and Tamil political leadership, which has not been the case ever since.[92] In 1919, major Sinhalese and Tamil political organizations united to form the Ceylon National Congress, under the leadership of Ponnambalam Arunachalam.[93] It kept pressing the colonial masters for more constitutional reforms. But due to its failure to appeal to the masses and the governor's encouragement for "communal representation" by creating a "Colombo seat" that dangled between Sinhalese and Tamils, the Congress lost its momentum towards the mid 1920s.[94] The Donoughmore reforms of 1931 repudiated the communal representation and introduced universal adult franchise (the franchise stood at 4% before the reforms). This step was strongly criticized by the Tamil political leadership, who realized that they would be reduced to a minority in the newly created State Council of Ceylon, which succeeded the legislative council.[95][96] In 1937, Tamil leader G. G. Ponnambalam demanded a 50-50 representation (50% for the Sinhalese and 50% for other ethnic groups) in the State Council. However, this demand was not met by the Soulbury reforms of 1944/45.

[edit] Post independence Sri Lanka

The Soulbury constitution ushered the Dominion status for Ceylon, delivering it independence on 4 February 1948.[97] The office of Prime Minister of Ceylon was created in advance of independence, on 14 October 1947, D. S. Senanayake being the first prime minister.[98] Prominent Tamil leaders like Ponnambalam and A. Mahadeva joined his cabinet.[95][99] Although the country gained independence in 1948, the British Royal Navy stationed at Trincomalee remained until 1956. 1953 hartal, against the withdrawal of the rice ration, resulted in the resignation of the then prime minister, Dudley Senanayake.[100] With the election of S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike to the prime ministership in 1956, Ceylon began moving towards better relations with the communist bloc. Bandaranaike's 3 year rule had a profound impact on the direction of the country. He emerged as the "defender of the besieged Sinhalese culture" and promised radical changes in the system.[101] He introduced the controversial Sinhala Only Act, recognising Sinhala as the sole official language of the government. Although it was partially reversed in 1958, the bill posed a grave concern for the Tamil community, which perceived their language and culture were threatened.[102][103] The Federal Party (FP) launched satyagraha against the move, which prompted Bandaranaike to reach an agreement (Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact) with S. J. V. Chelvanayakam, leader of the FP, to resolve the looming ethnic conflict.[104] However the pact was not carried out due to protests by opposition and the Buddhist clergy. The bill, together with various government colonisation schemes, contributed much towards the political rancour between Sinhalese and Tamil political leaders.[105] Bandaranaike was assassinated by an extremist Buddhist monk in 1959.[106]

The formal ceremony marking the start of self rule, with the opening of the first parliament at Independence Square.

The Government of J. R. Jayawardene swept to power in 1977, defeating the largely unpopular United Front government, towards its final years.[113] Jayawardene introduced a new constitution, together with a powerful executive presidency modelled after France, and a free market economy. It made Sri Lanka the first South Asian country to liberalise its economy.[114] However from 1983, ethnic tensions blew into on-and-off insurgency (see Sri Lankan Civil War) against the government by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (the LTTE, also known as the Tamil Tigers), a militant group emerged in early 1970s. Following the riots in July 1983, more than 150,000 Tamil civilians fled the island, seeking asylum in other countries.[115] Lapses in foreign policy resulted in neighbouring India strengthening the Tigers by providing arms and training.[116][117][118] In 1987, the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord was signed and Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) was deployed in northern Sri Lanka to stabilize the region by neutralising the LTTE.[119] The same year, the JVP launched its second insurrection in Southern Sri Lanka.[120] As their efforts did not become successful, IPKF was called back in 1990.[121]

Sri Lanka was affected by the devastating 2004 Asian tsunami, which left at least 35,000 people dead.[122] From 1985 to 2006, Sri Lankan government and Tamil insurgents held 4 rounds of peace-talks, none of them helping a peaceful resolution of the conflict. In 2009, under the Presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa the Sri Lanka Armed Forces defeated the LTTE, and re-established control of the entire country under the Sri Lankan Government.[123][124] The 26 year war caused up to 100,000 deaths.[125] Following the LTTE's defeat, Tamil National Alliance, the largest political party in Sri Lanka dropped its demand for a separate state, in favour of a federal solution.[126][127] The final stages of the war left some 294,000 people displaced.[128][129] According to the Ministry of Resettlement, most of the displaced persons had been released or returned to their places of origin, leaving only 6,651 in the camps as of December 2011.[130] Sri Lanka, emerging after a 26 year war, has become one of the fastest growing economies of the world.[131]

[edit] Geography

Main article: Geography of Sri Lanka

The island of Sri Lanka lies atop the Indian tectonic plate, a minor plate within the Indo-Australian Plate.[132] It is positioned in the Indian Ocean, to the southwest of the Bay of Bengal, between latitudes 5° and 10°N, and longitudes 79° and 82°E.[133] Sri Lanka is separated from the Indian subcontinent by the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait. According to the Hindu mythology, a land bridge existed between the Indian mainland and Sri Lanka. It now amounts to only a chain of limestone shoals remaining above sea level.[134] It was reportedly passable on foot up to 1480 AD, until cyclones deepened the channel.[135][136]The island consists mostly of flat-to-rolling coastal plains, with mountains rising only in the south-central part. Amongst these is the highest point Pidurutalagala, reaching 2,524 metres (8,281 ft) above sea level. The climate of Sri Lanka can be described as tropical and warm. Its position endows the country with a warm climate moderated by ocean winds and considerable moisture. The mean temperature ranges from about 17 °C (62.6 °F) in the central highlands, where frost may occur for several days in the winter, to a maximum of approximately 33 °C (91.4 °F) in other low-altitude areas. The average yearly temperature ranges from 28 °C (82.4 °F) to nearly 31 °C (87.8 °F). Day and night temperatures may vary by 14 °C (57.2 °F) to 18 °C (64.4 °F).[137]

Rainfall pattern of the country is influenced by Monsoon winds from the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal. The "wet zone" and some of the windward slopes of the central highlands receive up to 2,500 millimetres (98.4 in) of rain each month, but the leeward slopes in the east and northeast receive little rain. Most of the east, southeast, and northern parts of the country comprise the "dry zone", which receives between 1,200 mm (47 in) and 1,900 mm (75 in) of rain annually.[138] The arid northwest and southeast coasts receive the least amount of rain at 800 mm (31 in) to 1,200 mm (47 in) per year. Periodic squalls occur and sometimes tropical cyclones bring overcast skies and rains to the southwest, northeast, and eastern parts of the island. Humidity is typically higher in the southwest and mountainous areas and depends on the seasonal patterns of rainfall.[139]

Longest of the 103 rivers in the country is Mahaweli River, covering a distance of 335 kilometres (208 mi).[140] These waterways give rise to 51 natural waterfalls, having a height of 10 meters or more. The highest one is Bambarakanda Falls, with a height of 263 metres (863 ft).[141] Sri Lanka's coastline is 1,585 km long.[142] It claims to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles. This is approximately 6.7 times the country’s land area. The coastline and adjacent waters support highly productive marine ecosystems such as fringing coral reefs, shallow beds of coastal and estuarine seagrasses.[143] Sri Lanka inherits 45 estuaries and 40 lagoons too.[142] Country's mangrove ecosystem which spans over 7,000 hectares, played a vital role in buffering the force in the waves of 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.[144] The island is rich with minerals such as Ilmenite, Feldspar, Graphite, Silica, Kaolin, Mica and Thorium.[145][146] Existence of Petroleum in the Gulf of Mannar has also been confirmed and extraction attempts are underway.[147]

[edit] Flora and fauna

Main articles: Environment of Sri Lanka and Wildlife of Sri Lanka

Sri Lankan Elephant is one of three recognized subspecies of the Asian Elephant, and native to Sri Lanka. According to the 2011 elephant census, the country is home to at least 5879 elephants.[148]

The Sri Lankan Leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya) is an endangered subspecies of leopard native to Sri Lanka.

The Yala National Park in the southeast protects herds of elephant, deer, and peacocks, and the Wilpattu National Park, the largest national park in Sri Lanka, in the northwest preserves the habitats of many water birds, such as storks, pelicans, ibis, and spoonbills. The island has four biosphere reserves, Bundala, Hurulu Forest Reserve, the Kanneliya-Dediyagala-Nakiyadeniya, and Sinharaja.[154] Out of these, Sinharaja forest reserve is home to 26 endemic birds and 20 rainforest species, including the elusive Red-faced Malkoha, Green-billed Coucal and Sri Lanka Blue Magpie. The untapped genetic potential of Sinharaja flora is enormous. Out of the 211 woody trees and lianas so far identified within the reserve, 139 (66%) are endemic. The Total vegetation density, including trees, shrubs, herbs and seedlings has been estimated to be around 240,000 individuals per hectare.

In addition, Sri Lanka is home to over 250 types of resident birds (see List). It has declared several bird sanctuaries including Kumana.[155] During the Mahaweli Program of the 1970s and 1980s in northern Sri Lanka, the government set aside four areas of land totalling 1,900 km2 (730 sq mi) as national parks. However the country's forest cover, which was around 49% in 1920, had been fallen to approximately 24% by 2009.[156][157]

[edit] Politics

Main article: Politics of Sri Lanka

The old parliament building of Sri Lanka, near the Galle Face Green, now the Presidential Secretariat.

Current politics in Sri Lanka is a contest between two rival coalitions led by the centre-leftist and progressivist United People's Freedom Alliance (UPFA), an offspring of Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), and the comparatively right-wing and pro-capitalist United National Party (UNP).[163] Sri Lanka is essentially a multi-party democracy with many smaller Buddhist, socialist and Tamil nationalist political parties. As of July 2011, the number of registered political parties in the country is 67.[164] Out of these, the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), established in 1935 is the oldest.[165] UNP, established by D. S. Senanayake in 1946, was considered to be the largest single political party until recently.[166] It is the only political group which had a representation in all parliaments since the independence.[166] SLFP was founded by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, who was the Cabinet minister of Local Administration, before he left the UNP in July 1951.[167] SLFP registered its first victory in 1956, defeating the ruling UNP in 1956 Parliamentary election.[167] Following the parliamentary election in July 1960, Sirimavo Bandaranaike became the prime minister and the world's first elected female head of state.[168]

G. G. Ponnambalam, the Tamil nationalist counterpart of S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike,[169] founded the All Ceylon Tamil Congress (ACTC) in 1944. As an objection to Ponnambalam's cooperation with D. S. Senanayake, a dissident group led by S.J.V. Chelvanayakam broke away in 1949 and formed the Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK) aka Federal Party. It was the main Tamil political party in Sri Lanka for next 2 decades.[170] Federal party advocated a more aggressive stance vis-à-vis the Sinhalese.[171] With the constitutional reforms of 1972, these parties created a common front, the Tamil United Front (later Tamil United Liberation Front). Tamil National Alliance, formed in October 2001 is the current successor of these Tamil political parties which had undergone much turbulences as Tamil militants' rise to power in late 1970s.[171][172] Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, a Marxist-Leninist political party, founded by Rohana Wijeweera in 1965, serves as the 3rd force in the current political context.[173] It endorses radical leftist policies, with respect to the traditionalist leftist politics of LSSP and Communist Party.[171] Founded in 1981, Sri Lanka Muslim Congress is the largest Muslim political party in Sri Lanka.[174]

[edit] Government

Main articles: Constitution of Sri Lanka and Elections in Sri Lanka

| Flag | Lion Flag |

| Emblem | Gold Lion Passant |

| Anthem | Sri Lanka Matha |

| Butterfly | Troides darsius |

| Bird | Sri Lanka Junglefowl |

| Flower | Red and Blue Water Lily |

| Tree | Ceylon Ironwood (Nā) |

| Game | Volleyball |

The Sri Lankan government has 3 branches:

- Executive: The President of Sri Lanka is the head of state, the commander in chief of the armed forces, as well as head of government, and is popularly elected for a six-year term.[178] In the exercise of duties, the President is responsible to the parliament. The President appoints and heads a cabinet of ministers composed of elected members of parliament.[179] President is immune from legal proceedings while in office in respect of any acts done or omitted to be done by him either in his official or private capacity.[180] With the 18th amendment to the constitution in 2010, the President has no term limit, which previously stood at 2.[181]

- Legislative: The Parliament of Sri Lanka, is a unicameral 225-member legislature with 196 members elected in multi-seat constituencies and 29 by proportional representation.[182] Members are elected by universal (adult) suffrage based on a modified proportional representation system by district to a six-year term. The president may summon, suspend, or end a legislative session and dissolve Parliament any time after it has served for one year. The parliament reserves the power to make all laws.[183] President's deputy, the Prime Minister, leads the ruling party in parliament and shares many executive responsibilities, mainly in domestic affairs.

- Judicial: Sri Lanka's judiciary consists of a Supreme Court - the highest and final superior court of record,[183] a Court of Appeal, High Courts and a number of subordinate courts. Its highly complex legal system reflects diverse cultural influences.[184] The Criminal law is almost entirely based on British law. Basic Civil law relates to the Roman law and Dutch law. Laws pertaining to marriage, divorce, and inheritance are communal.[185] Due to ancient customary practices and/or religion, the Sinhala customary law (Kandyan law), the Thesavalamai and the Sharia law too are followed on special cases.[186] The President appoints judges to the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, and the High Courts. A judicial service commission, composed of the Chief Justice and two Supreme Court judges, appoints, transfers, and dismisses lower court judges.

[edit] Administrative divisions

Main articles: Provinces of Sri Lanka, Districts of Sri Lanka, and Divisional Secretariats of Sri Lanka

See also: List of cities in Sri Lanka and List of towns in Sri Lanka

For administrative purposes, Sri Lanka is divided into 9 provinces[187] and 25 districts.[188]- Provinces

| Administrative Divisions of Sri Lanka | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Capital | Area (km²) | Area (sq mi) |

Population | |||

| Central | Kandy | 5,674 | 2,191 | 2,423,966 | |||

| Eastern | Trincomalee | 9,996 | 3,859 | 1,460,939 | |||

| North Central | Anuradhapura | 10,714 | 4,137 | 1,104,664 | |||

| Northern | Jaffna | 8,884 | 3,430 | 1,311,776 | |||

| North Western | Kurunegala | 7,812 | 3,016 | 2,169,892 | |||

| Sabaragamuwa | Ratnapura | 4,902 | 1,893 | 1,801,331 | |||

| Southern | Galle | 5,559 | 2,146 | 2,278,271 | |||

| Uva | Badulla | 8,488 | 3,277 | 1,177,358 | |||

| Western | Colombo | 3,709 | 1,432 | 5,361,200 | |||

- Districts and local authorities

There are 3 other types of local authorities: Municipal Councils (18), Urban councils (13) and Pradeshiya Sabha (aka Pradesha Sabhai, 256).[196] Local authorities were originally based on the feudal counties named korale and rata, and were formerly known as 'D.R.O. divisions' after the 'Divisional Revenue Officer'.[197] Later the D.R.O.s became 'Assistant Government Agents' and the divisions were known as 'A.G.A. divisions'. These Divisional Secretariats are currently administered by a 'Divisional Secretary'.

| Largest cities of Sri Lanka (2010 Department of Census and Statistics estimate)[198] |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Colombo  Kandy |

Rank | City Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | City Name | Province | Pop. |

Galle  Jaffna |

||

| 1 | Colombo | Western | 685,246 | 11 | Batticaloa | Eastern | 97,648 | ||||

| 2 | Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia | Western | 234,559 | 12 | Katunayake | Western | 92,469 | ||||

| 3 | Moratuwa | Western | 204,849 | 13 | Battaramulla | Western | 85,348 | ||||

| 4 | Negombo | Western | 144,995 | 14 | Jaffna | Northern | 84,416 | ||||

| 5 | Trincomalee | Eastern | 126,902 | 15 | Dambulla | Central | 77,148 | ||||

| 6 | Kotte | Western | 126,872 | 16 | Maharagama | Western | 75,127 | ||||

| 7 | Kandy | Central | 120,087 | 17 | Dalugama | Western | 74,428 | ||||

| 8 | Vavuniya | Northern | 108,834 | 18 | Kotikawatta | Western | 72,858 | ||||

| 9 | Kalmunai | Eastern | 104,985 | 19 | Anuradhapura | North Central | 68,244 | ||||

| 10 | Galle | Southern | 97,807 | 20 | Kolonnawa | Western | 64,707 | ||||

[edit] Foreign relations and military

Main articles: Foreign relations of Sri Lanka and Sri Lanka Armed Forces

President Mahinda Rajapaksa with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, at St. Petersburg Economic Forum, in June 2011.

One of the two parties that have governed Sri Lanka since its independence, UNP, is traditionally biased towards the West, with respect to its left-leaning counterpart, SLFP.[199] Sri Lankan Finance Minister J. R. Jayewardene, together with the then Australian Foreign Minister Sir Percy Spencer, proposed the Colombo Plan at Commonwealth Foreign Minister’s Conference held in Colombo in 1950.[200] In a remarkable move, Sri Lanka spoke in defence for a free Japan, while many countries were reluctant to allow a free Japan, at the San Francisco Peace Conference in 1951, and refused to accept the payment of reparations for that damage it had done to the country during World War II, that would harm Japan's economy.[201] Sri Lanka-China relations started as soon as the PRC was formed in 1949. Two countries signed an important Rice-Rubber Pact in 1952.[202] Sri Lanka played a vital role in Asian–African Conference in 1955, which was an important step toward the crystallization of the NAM.[203] The Bandaranaike government of 1956 significantly digressed from the pro-western policies of UNP government. Sri Lanka immediately recognised the new Cuba under Fidel Castro in 1959. Shortly after, Cuba's legendary revolutionary Ernesto Che Guevara paid a visit to Sri Lanka.[204] The Sirima-Shastri Pact of 1964[205] and Sirima-Gandhi Pact of 1974[206] were signed between Sri Lankan and Indian leaders in an attempt to solve the long standing dispute over the status of plantation workers of Indian origin. In 1974, Kachchatheevu, a small island in Palk Strait was formally ceded to Sri Lanka.[207] By this time, Sri Lanka was strongly involved in the NAM and Colombo held the fifth NAM summit of 1976.[208] The relationship between Sri Lanka and India became tensed under the government of J. R. Jayawardene.[121][209] As a result, India intervened in Sri Lankan Civil War and subsequently deployed the Indian Peace Keeping Force in 1987.[210] In the present, Sri Lanka enjoys extensive relations with China,[211] Russia[212] and Pakistan.[213]